Lumpy skin disease: Control and prevention of lumpy skin disease

Learn how to control lumpy skin disease (LSD)Part of Series:

< Previous Article in Series

Editors note: The following content is an excerpt from Lumpy Skin Disease: a field manual for veterinarians which is designed to enhance awareness of lumpy skin disease and to provide guidance on early detection and diagnosis for private and official veterinary professionals (in the field and in slaughterhouses), veterinary paraprofessionals and laboratory diagnosticians.

Prevention of LSD

- The best protection comes from prophylactic vaccination of the entire cattle population, carried out well in advance in at-risk areas.

- Movements of cattle inside the country and across borders should be strictly controlled or totally banned. Authorized cattle movements should be accompanied by a veterinary certificate including all data concerning the animals’ origins, and animal health guarantees.

- In affected villages, cattle herds should be kept separate from other herds by avoiding communal grazing, if possible without animal welfare issues. However, in some cases the whole village forms a single epidemiological unit and then the feasibility of separation has to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

- Movements of vaccinated animals can be allowed within a restricted zone within a country after it has been established that full immunity has been provided by a vaccine with proven efficacy (28 days after vaccination).

- Cattle should be treated regularly with insect repellents to minimize the risk of vector transmission of the disease. This measure cannot fully prevent transmission but may reduce the risk.

Currently available vaccines, selection of an effective vaccine, adverse reactions and vaccination strategy

Only live vaccines are currently available against LSDV. No Differentiation of Infected from Vaccinated Animals (DIVA) vaccines have been developed against LSD. Live vaccines are authorized for use in cattle in Africa, but in other currently affected regions specific authorization is required prior to their use.

Annual vaccination is recommended in affected countries, and harmonized vaccination campaigns across regions provide the best protection. Calves from naïve mothers should be vaccinated at any age, while calves from vaccinated or naturally infected mothers should be vaccinated at 3-6 months of age.

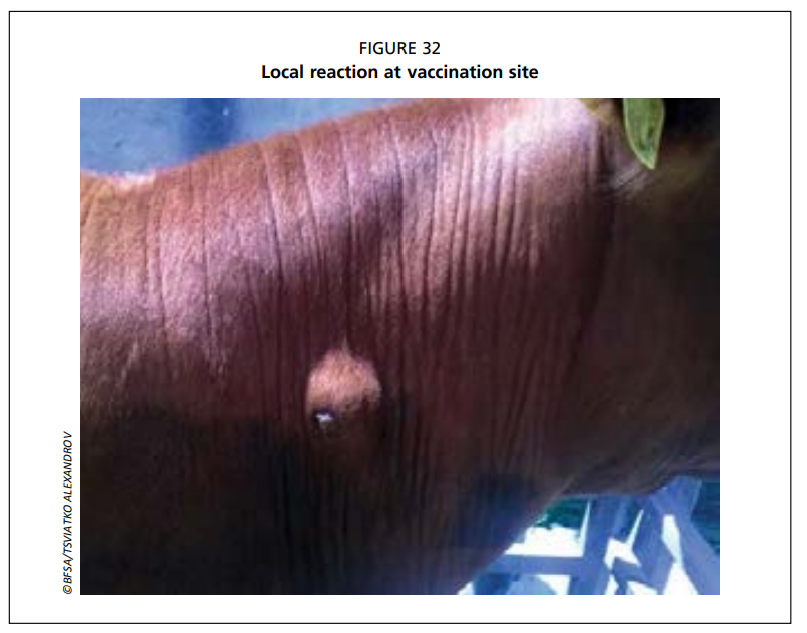

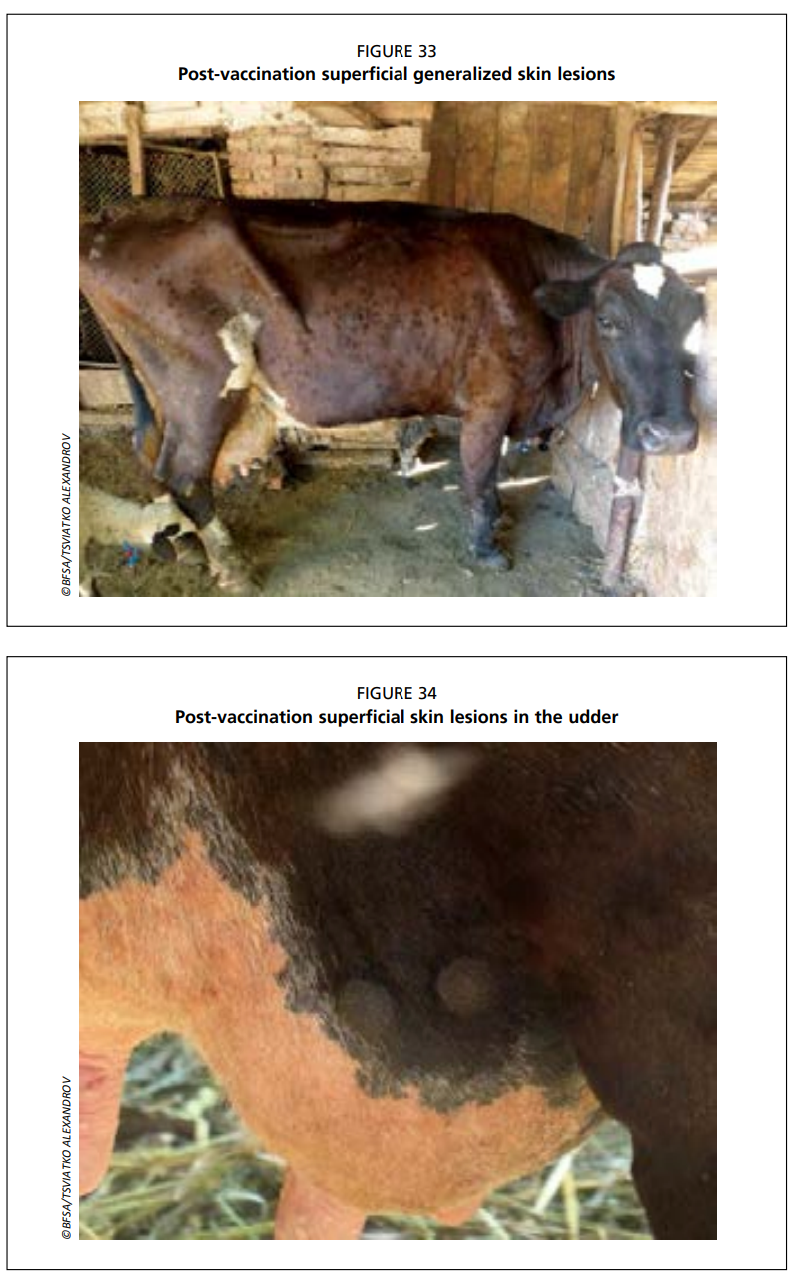

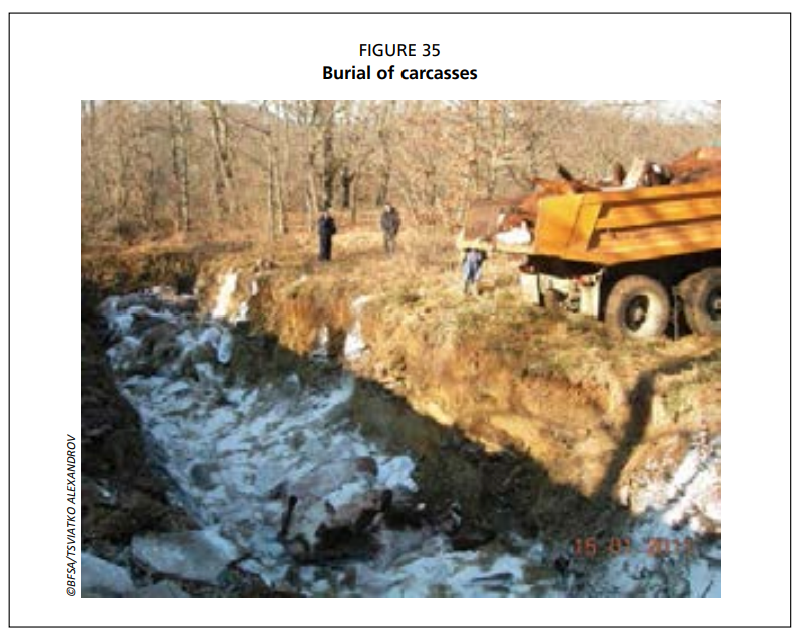

Regional harmonized vaccinations are recommended and should be carried out before large-scale movements of cattle, for example prior to the onset of seasonal grazing. Live, attenuated LSDV vaccines may cause mild adverse reactions in cattle. Local reaction at the vaccination site (Fig. 32) is common and acceptable as it shows that the attenuated vaccine virus is replicating and producing good protection. Common adverse reactions include temporary fever and a brief drop in milk yield. Some animals may show mild generalized disease.

However, skin lesions caused by attenuated virus are usually superficial, clearly smaller, and different from those caused by the fully virulent field strain (Figs. 32-34). They disappear within 2-3 weeks without converting into necrotic scabs or ulcers. In practice, vaccination campaigns are often started when the virus is already widespread in the region. Development of full protection from the vaccine takes approximately three weeks. During this time, cattle may still get infected by the field virus, and may show clinical signs despite being vaccinated.

Some animals may also be incubating the virus when vaccinated, and in such cases clinical signs are detected less than ten days after vaccination.

Attenuated LSDV vaccines

Currently, there are three vaccine producers manufacturing attenuated LSDV vaccines. Live, attenuated LSDV vaccines provide good protection in cattle if 80 percent vaccination coverage is attained. In practice, all animals need to be vaccinated, including small calves and pregnant cows. Regional vaccination campaigns should be preferred to ring vaccination.

Attenuated SPPV vaccines

Sheep pox virus vaccines have been used in cattle against LSDV in those regions where LSD and SPP are both present. As the protection provided by SPPV vaccines against LSDV is believed to be partial, selection of the vaccine should always be based on demonstrated efficacy of the vaccine against LSDV by a challenge trial carried out in a controlled environment.

If acceptable efficacy of the SPPV/GTPV vaccines is demonstrated, SPP vaccines can be used provided that full vaccination coverage and other appropriate control measures are in place.

Attenuated Gorgan GTPV vaccine

Commercially available GTPV Gorgan strain has been demonstrated to provide equal protection against LSD as the LSDV vaccines (Gari et al., 2015). Gorgan GTPV vaccine is a good, cost-effective alternative in those countries where GTP and LSD overlap.

Cattle movement controls

Movements of unvaccinated cattle represent the major risk factor for disease spread. During an LSD outbreak, movements of cattle should be strictly regulated, but in practice effective control is often difficult. Appropriate legal powers should be in place to allow veterinary authorities to act as soon as any illegal transport of cattle is detected. Trade in live cattle must be banned immediately upon suspicion and/or confirmation of the disease. In many regions, unauthorized transboundary trade occurs despite restrictions, underlining the importance of regional vaccination.

Severe penalties should be applied for illegal movements. Where nomadic and seasonal farming is practiced, cattle should be vaccinated at least 28 days before going on the move. Movements of unvaccinated breeding animals should not be allowed during outbreaks. Slaughter of cattle should be allowed only in slaughterhouses located within restricted zones because open transport vehicles waiting at their destination may give blood-feeding, flying vectors sufficient time to transmit the virus.

Stamping-out policies and disposal of carcasses

In many affected countries, either total or partial stamping-out policies have been implemented. In countries with limited resources, no kind of stamping out may be affordable. The efficacy of these methods is widely discussed by experts and decision-makers. According to the EFSA urgent advice on lumpy skin disease, vaccination has a greater impact in reducing LSDV spread than any stamping-out policy (EFSA, 2016). Stamping out should always be combined with a sound compensation programme. Without timely and adequate compensation, cattle owners are likely to object to having their animals killed, leading to reduced reporting and the dissemination of the disease through illegal movements of infected animals.

The long-term effect of stamping out on farmers’ livelihoods, public perception and media involvement should be considered in any decisions. Total stamping out has the best chance of success and is practical if the first incursion of the disease in a country or defined region is detected and notified without delay, and the threat of repeated incursions is low. Because identifying particularly mild and early cases may be extremely challenging, several weeks may elapse between initial infection and detection of the disease, allowing spread of the virus by vectors. In addition, the epidemiological unit involved may often be a whole village rather than a single farm, reducing the efficacy of total or partial stamping-out policies. Partial stamping out by culling animals with clinical disease may reduce infectivity, but is unlikely to end an outbreak on its own.

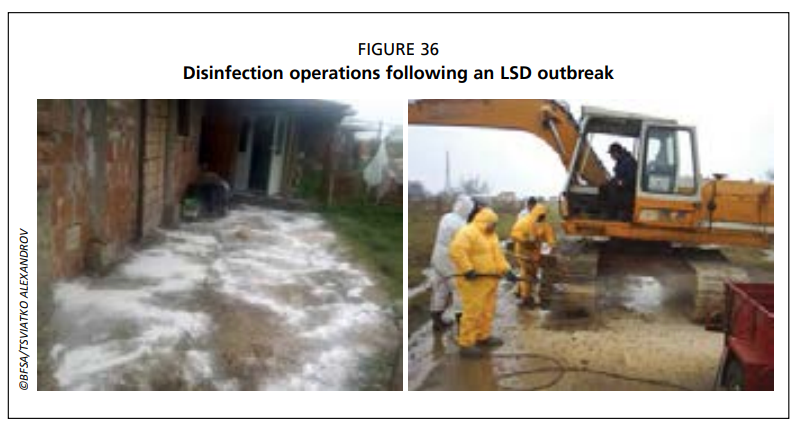

Timely, large-scale vaccination across the affected regions using an effective vaccine will bring an outbreak to a total halt regardless of the chosen stamping-out policy. However, the effect of the vaccination campaign may be felt earlier if total stamping out is undertaken. When a stamping-out policy is implemented, culling and disposal of carcasses should take place as soon as possible in compliance with all animal welfare and safety requirements.

Disposal by burial or burning should follow national rules on environmental protection. In some countries, these practices may not be allowed at all. Appropriate methods for culling cattle are premedication and injection with barbiturates or other drugs, followed by captive-bolt stunning and pithing or free bullet. Disposal of carcasses should be conducted by burial, burning or rendering, according to national procedures.

Importantly, regardless of the stamping-out policy selected, severely affected animals should always be removed from the herd because they serve as a constant source of contamination for biting and blood-feeding vectors. In the same way, no animal showing any clinical signs of LSD should be sent to a slaughterhouse, but should be culled and disposed of either on-site or at an appropriate rendering plant. It should be borne in mind that farmers will benefit from replacement of culled animals with healthy, immunized ones as a herd usually needs several months to recover and is unlikely to return to the same level of production as before LSD infection.

Cleaning and disinfection of personnel, premises and environment

Lumpy skin disease virus is very stable and survives well in extremely cold and dry environments within the pH range 6.3-8.3. Infected animals shed scabs from skin lesions. Inside the scabs, the virus may remain infectious for several months. Thorough cleaning and disinfection with appropriate products should be performed on affected farms, trucks, premises and potentially contaminated environments.

Personnel should also undergo disinfection. Although LSDV is sensitive to most disinfectants and detergents, in order to effectively decontaminate animal facilities and holdings, mechanical removal of surface material such as dirt, manure, hay and straw is required beforehand. The disinfectant selected must be able to penetrate any organic material surrounding the infectious virus in the environment. FAO provides practical recommendations for decontamination of premises, equipment and the environment in the Animal Health Manual on Procedures for Disease Eradication by Stamping Out (FAO, 2001).

Insect control on animals and in the environment

Efficient insect control on cattle or in holdings may reduce the rate of mechanical transmission, but cannot totally prevent it, particularly where cattle are free-roaming or kept in fenced pastures. Anti-mosquito nets can be considered in cases when cattle are permanently kept indoors. The application of spot-on repellents can protect cattle from insects and ticks for short periods.

When insecticides are used, withdrawal times for milk and meat need to be considered. Large-scale use of insecticides in the environment is not recommended as it may be harmful to the ecological balance, and to other useful insects such as honeybees. Moreover, the risk to the environment is not fully understood. Limiting vector breeding sites such as standing water sources, slurry and manure, and improving drainage in holdings are sustainable, affordable and environmentally friendly ways of reducing the number of vectors on and around cattle.

Biosecurity measures at holdings

In the event of LSD entering a country, farm biosecurity should be raised to the highest feasible level, taking into consideration the limits of the epidemiological unit in each case. As the disease is spread by vectors, such measures may not totally prevent an incursion, but the risk can be reduced. Purchase of new animals that are either incubating the disease or are viraemic without exhibiting any symptoms presents a major risk of introducing the disease into a naïve herd. Introduction of new animals into herds should therefore be limited.

Stock should be bought only from trusted sources. New animals should be examined and declared free of clinical signs prior to movement and on arrival, and should be kept separated/quarantined from the herd for at least 28 days. Farm visits should be restricted to essential services with entry points to properties limited. All visitor vehicles and equipment should be cleaned in a wash-down bay when entering farms. Boots should also be cleaned or, alternatively, shoe covers should be worn. Visitors entering farms should wear clean protective clothing.

Target audience for awareness

Awareness campaigns should be targeted at official and private veterinarians, both field and abattoir, veterinary students, farmers, herdsmen, cattle traders, cattle truck drivers and artificial inseminators. Cattle truck drivers are in a particularly good position to identify infected animals on farms and in slaughterhouses and at cattle collection and resting stations, and to notify veterinary authorities of any clinical suspicion as soon as possible.

Surveillance programmes

Surveillance programmes are based on active and passive clinical surveillance and laboratory testing of blood samples, nasal swabs, or skin biopsies collected from suspected cases. As there are no DIVA vaccines against LSD, serological surveillance is of no use in affected countries or zones where the entire cattle population is vaccinated. However, serology can be used whenever the presence of unnoticed/unreported outbreaks are investigated in disease-free regions either bordering, or in close proximity to, affected regions with unvaccinated cattle. In such regions, the presence of seropositive animals can be considered as an indication of recent outbreaks.

Reference:

Tuppurainen, E., Alexandrov, T. & Beltrán-Alcrudo, D. 2017. Lumpy skin disease field manual – A manual for veterinarians. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 20. Rome. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 60 pages.