Relieving heat stress in dairy cattle

Dairy cattle in warm climates are at risk of heat stress, which can adversely affect both their welfare and milk production. To investigate the effects of heat stress on cattle, Dr Amanda Stone of Mississippi State University, USA, uses Precision Dairy Monitoring Technologies. Some of these technologies allow for continuous monitoring of the body temperature of cattle. Recently, Dr Stone’s research inspired the design of an innovative sprinkler system, which has been shown to effectively minimise the effects of heat stress in pastured dairy cattle.

Over the last few decades, the dairy industry has made great improvements in animal welfare standards, including in developing a better quality of life for livestock. At the same time, various technological and scientific developments have allowed farmers to get more from their animals: more milk, more eggs, more meat, and so on. Balancing animal welfare standards with the drive for higher production yields is an ongoing challenge for both farmers and agricultural researchers.

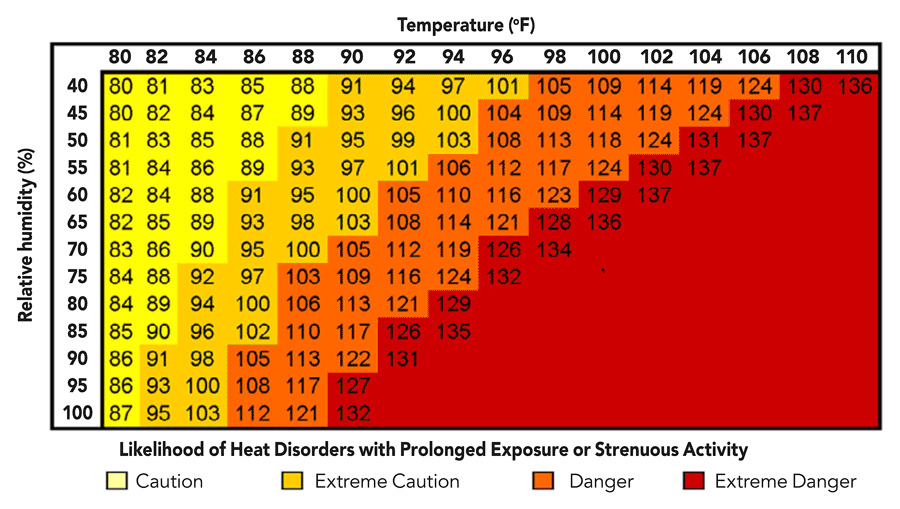

Welfare issues in farmed animals can vary, depending on the chosen farming method, local climate and environment, and the particular breed of animal, among other things. In dairy cattle, heat stress can be a particular problem. Like other animals, cattle suffer from heat stress when they are unable to properly regulate their body temperature. Cattle need to be able to dissipate the heat they generate through metabolism into their environment. When the air temperature and humidity levels are high, or cattle are over-exposed to intense sunlight, it becomes very difficult for the animals to lose excess metabolic heat. While the risk of heat stress is highest in tropical and subtropical regions, it can affect cattle anywhere in the world.

Unfortunately, the problem of heat stress has been exacerbated by the drive to increase milk yields; more milk production demands greater metabolic activity, producing more heat that the cow must lose in order to balance its body temperature. In addition, climate change means that global temperatures have risen, and are expected to continue to rise, increasing the risk of overheating for animals kept outdoors.

Heat stress can affect the health and welfare of cattle in several different ways. It can suppress the cows’ immune systems, leading to an increased risk of diseases like mastitis (inflammation of the udder tissue), and cause reproductive problems. Cows that are struggling to lower their body temperature will spend more time standing rather than lying down – dairy cows need to spend 10-12 hours a day lying down to maintain good health. Finally, the cumulative effects of heat stress tend to both reduce milk yield and alter the composition of the milk; stressed cows produce milk with a lower protein and fat content.

A technological solution to a welfare problem?

With the potential for heat stress likely to continue to increase, there is a clear need for innovative ways to address this problem, to both ensure the welfare of dairy cattle and, if possible, maintain milk yields.

Dr Amanda Stone of Mississippi State University focuses her research on the use of Precision Dairy Monitoring Technologies (PDMT) to evaluate heat stress in dairy cattle. This system incorporates a variety of different technologies to measure physiological, behavioural and production factors in individual animals. More broadly, PDMT has several potential uses; for example, farmers can use PDMT to assess whether cows are in oestrus or about to give birth. The technology could also indicate animals that might be at risk of disease, allowing farmers to take action before the disease becomes clinical.

"Using PDMT to assess how, when, and why heat stress occurs should help in identifying ways to relieve the condition."

Using PDMT to tackle heat stress

In southeastern USA, where Dr Stone is based, dairy cattle can spend as much as half of every year in a state of heat stress. This clearly impacts both the welfare of the cows and their milk yield. Using PDMT to assess how, when, and why heat stress occurs, should help in identifying ways to relieve the condition. Fortunately, a useful feature of several PDMT is the ability to monitor cattle body temperature on a 24-hour basis, something that would otherwise be impossible.

Recently, Dr Stone used PDMT as part of an investigation into the effects of heat stress on dairy cows. During the study, a herd of 27 cows was divided into nine groups. Three groups received three different treatments and each study was then replicated two more times. Each group was kept in outdoor pens under different environmental conditions: either in shade (the pen was equipped with a portable sunshade, large enough to shelter all the cows), with a sprinkler (enclosures had a sprinkler system which stayed on for the duration of the study) or with no special heat-reduction measures (the control group).

Dr Stone and her colleagues carried out a range of measurements and observations during the study. These included the ambient temperature and humidity, and the milk yield, milk fat and protein content, body temperature, respiration rate and body condition for each cow. In addition, three times a day the team assessed the cows for signs of heat stress, including an increased respiration rate and certain behaviours. Any animals showing signs of severe or persistent heat stress were removed from the study, examined by a veterinarian, and cared for closely until they returned to their baseline temperature.

"Sprinkler systems are an effective way to improve the welfare of cattle at risk of heat stress."

The researchers found that the cows with access to sprinklers had a significantly lower respiration rate and were less affected by heat stress than those which received no form of cooling. Cows in the sprinkler group also had significantly lower hygiene scores (i.e. were cleaner) than either of the other treatment groups. The results showed that sprinkler systems are an effective way to improve the welfare of cattle at risk of heat stress. This effect could be further enhanced by the provision of shade.

The Mississippi Mister

As a result of their research into heat stress, Dr Stone and her colleagues have designed a new type of sprinkler that should help to improve both welfare and production yield in dairy cattle: the Mississippi Mister. Compared to the center pivot, a sprinkler system that is normally utilised to irrigate crops but can also be used to cool cows, the Mississippi Mister is both cheaper and more portable. It can be built relatively easily using readily available materials, such as PVC pipes, Teflon tape, and zip ties. Constructing the Mister from PVC means that it is light: this is important, as it needs to be moved every few days to prevent the ground becoming too muddy (which could increase the risk of mastitis).

Managing heat stress in cattle in hot regions, such as the south-eastern USA, will be an ongoing challenge. The research carried out by Dr Stone and her team, using PDMT, makes an important contribution to efforts to both support the welfare, and maintain the production yield, of dairy cattle at risk of heat stress. In developing the Mississippi Mister, Dr Stone has successfully used her research to create a real, practical way to tackle the problem of heat stress in dairy cattle.