Poaching: How To Avoid It?

The risk of poaching is a fact of life on most Irish soils and in most seasons of the year, says Adrian van Bysterveldt, Teagasc, Moorepark Dairy Production Research Centre, Fermoy, County Cork.The cost to a farmer is as much in increased stress as it is in financial costs and the reduced pasture growth may result in the need to purchase additional much more expensive feeds. Most good farmers are aware of this cost but fears about poaching are the primary reason that farmers house their cows for a long time. Financial analysis shows that if farmers have the confidence and ability to keep cows out on grass earlier and later in the season, then there is an additional profit of over €2.50/cow/day.

A single poaching event will reduce pasture growth over the next few months by 20 to 40 per cent, the more severe the poaching the greater the reduction in growth and the longer this will continue to occur. A poaching event will also make this area of the farm much more susceptible to future poaching events which will often be even more severe.

The cost effective remedies for poaching are few and take a long time to rectify the damage so the essential approach is to take sensible strategic and management precautions to avoid poaching in the first instance. On occasion, the weather is simply too severe and too prolonged to avoid poaching, but making the effort to minimise it will have a dramatic impact on the overall cost to the farm.

Strategies to avoid poaching (in order of importance)

Infrastructure investment

- Drainage

- Standoff facilities

- Paddock shape

- Number and location of entrances

- Wide crowned cow tracks that shed water and stay clean

- Stand off facilities

- Cow type

- Pasture species

Management

- On/off grazing

- Strip grazing using a back fence

- Using narrow temporary lanes for cows to access the back of paddocks

- Closely watching reliable weather forecasts

- Selection of paddocks for grazing in wet weather

- Setting up longest pasture covers at calving on the driest ground

Investment in effective drainage remains the most important strategy to avoid poaching. Different soil types and localities require different types of drainage and there is no value at all in taking shortcuts and not doing it properly. Investment in the correct drainage strategy will give a solid return over many decades.

In wet land open drains should be a feature of all of the boundaries of the paddock. The wetter the land the smaller the paddocks should be and therefore the more drains there should be. Drains need to be kept free of vegetation which impedes water flow and each drain must have enough fall to allow it to shed water away from the farm.

Hump and hollow the land surface fits in well with open drains where the soil is heavy clay. The objective here is to provide a contour so that during rain water does not pond on the surface but easily follows slope to the open drains. This is necessary because clay tile and other sub surface drainage systems are ineffective in these heavy clay soils.

Clay tiles or perforated drainage pipes along with drainage gravel and cross mole ploughing is a very effective system on moderately draining land as long as the whole package is properly done. There needs to be fall on the clay pipes or perforated piping so that water entering it moves steadily to the open drains. Drainage metal above these structures improves the ability of the pipes to draw surplus water from the soil profile. Mole ploughing can be a very useful addition to this but it must be done at the end of the spring and just before a dry period in the summer. The soil must be moist enough to form a mole when a mole plough is dragged through the soil but for this to become effective the clay sides of the cut and mole have to dry and crack so that moisture can move into the mole. If these moles intersect with the drainage gravel above a perforated pipe the water is quickly drained from the paddock. This also means that moles can be pulled on an angle across the slope and because they only have a short run to the drainage gravel they do not have to have as much fall as the lower piping.

Deep-ripping to shatter an impervious pad is only an option in limited situations where test holes confirm a shallow pad with free draining gravels beneath. Ripping typically has to be done at the end of a dry summer otherwise the land is to soft to allow this operation and it the water table is not also lowered the pad will quickly reform.

Tapping out the head of springs is an art form and required patience. This is best done with an open drain dug along the side of the wet area and curving around the top of the wet area, where this drain may need to be quite deep to intercept the source of the water. It is best to leave this as an open drain for several years so that the wet area properly dries out and it is clear that all the spring heads have been tapped. Once this phase is complete large drainage pipes can be laid directly to the source of each spring and then covered with some drainage gravel and the drain filled. Tapping springs can change large troublesome areas of paddocks, often on the side of hills.

Standoff facilities can be located centrally which is the norm in Ireland but smaller hard surface (compacted stone) ones can be located at the ends of cow lanes so that cows can be stood off for short periods with out having to walk long distances. Paddock shape can have a huge impact on the ability to avoid poaching.

Paddocks on wet land should be longer along the cow lanes then they are away from the lanes. This allows the use of multiple entrances and exists, and makes strip grazing much easier. It also allows for cows to enter paddocks where they will not cross a particularly wet/soft area on the way to the majority of the feed in the paddock. The extra investment in cow lanes also means that each lane gets less pressure and lasts longer especially if they are properly constructed with well compacted rock that has been shaped so that the lane has a crown. If any build up of material is regularly removed from the sides these cow lanes shed water and dry quickly. This greatly reduces the tramping of mud into paddocks which will soil pasture and cause stock to become unsettled.

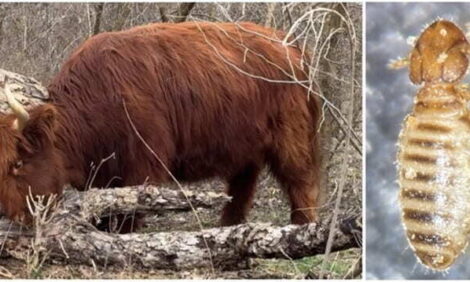

The weight of cows has a great bearing on how quickly soils will poach. Small cows do not have proportionally smaller feet and so the down pressure that they exert on the soil surface is much less. In marginal conditions this is frequently the difference between poaching and not poaching. Breeding to select for small cows within a desired breed is an essential tool and ideally this should be taken further through cross breeding with an even smaller dairy cow.

The selection of particular pastures for wetter paddocks is also a very useful option. Some pasture variety such as Timothy are very tolerant to poaching damage but are much more difficult to establish and require different management than ryegrass pastures. Even within ryegrasses there is a great deal of variation. Varieties that are very dense tillering are ideal for wetter paddocks as they provide more cover between the cow’s foot and the soil. They often are also slower growing in the winter and early spring and so require less grazing during the worst of the weather. Tetraploid ryegrasses often result in more open pastures and often have improved autumn, winter and early spring growth. These varieties should only be sown on the driest paddocks so that the extra growth can actually be utilised.

Grazing stock during the day and then keeping them in at night has been practiced for a long time but recent work at Moorepark shows that On/off grazing is much more effective if it is for short periods of 3 – 4 hours both at limiting pasture damage (to less than 5 per cent) and maintaining cow intakes (at 98 per cent of a full 24-hour grazing). In the case of milking cows each three-hour period grazing should occur after each milking with some consideration of the immediate weather at that time i.e., if it raining heavily delay the grazing until the rain eases, but before the next milking. It is also essential that these cows do not get any additional feed while they are not grazing. This makes then hungry and focused on grazing rather than walking around making mud.

Strip grazing is also a very effective tool. Research showed that strip grazing using a backing fence reduced the damage on the whole paddock by over 50 per cent. This can also be improved if the groups of cows are reduced and the area of new pasture given is a square of sheltered from the wind.

The use of narrow (one cow wide) temporary lanes in a paddock to get the herd to the new grass at the back of a paddock is also very effective at limiting the damage especially when doing on/off grazing. This confines the damage to a very small area and even though it is severe the impact on the total yield of the paddock is very small. It also reduces the area to be fixed. There are farmers with herds of 350 cows using this very effectively.

Fixing poaching

Machinery manufactures offer lots of options that are supposed to reduce compaction and fix poaching. In controlled trials the impact of these machines has been marginal at best and not enough to justify the cost of the machinery or the time on the tractor. The only economically effective option is to sow more ryegrass to replace the plants that have been lost. In minor to mild poaching cases the plant is able to repair itself reasonably quickly and tiller density quickly returns back to normal. In mild to moderate poaching events grass seed should be broadcast as soon as the ground has firm up. Often the best time to do it is just before the cows come to graze the paddock again. The cow’s feet push the seed into the ground and so it quickly germinates. By the next grazing the new grass plants will be still too small to be grazed by the cows but they will respond to receiving direct light and will grow quickly. The addition of more grass seed will have a big impact on reducing the invasion of weeds. By the third grazing they will by a normal part of the sward.

The use of a light roller which will just flatted the worst of the foot marks will not worsen or improve the pasture growth rates but it will make the paddock more usable for making silage and much easier to measure the amount of grass in the paddock.

After severe poaching events the paddock will need to be properly re-seeded. A pasture will return without doing anything but it will be dominated by weed grasses that will produce much less usable food for stock. Reseeding is an expensive exercise and not economically sustainable if large areas of the farm (more that 20 per cent) need to be fixed in this way each year.

Conclusion

Poaching in most cases is a problem that requires a farmer to use all the tools available to him to control. By using the full range of structural and management options most land can be effectively farmed and poaching avoided or limited and stock given the opportunity to graze more days of the year which is a big boost to farmer profit and greatly reduces the farmer work load.

The issue of land being damaged is no longer acceptable to the urban population and all round the world, land that can not be sufficiently drained or managed to prevent repeated severe poaching and erosion, is being taken and removed from agriculture.